A Conversation with Rina Garcia Chua

Green is everywhere here.

Plants roll and melt off shelves and line the windowsills, while two skinny pigs wheek for their afternoon vegetables in Popcorn City.

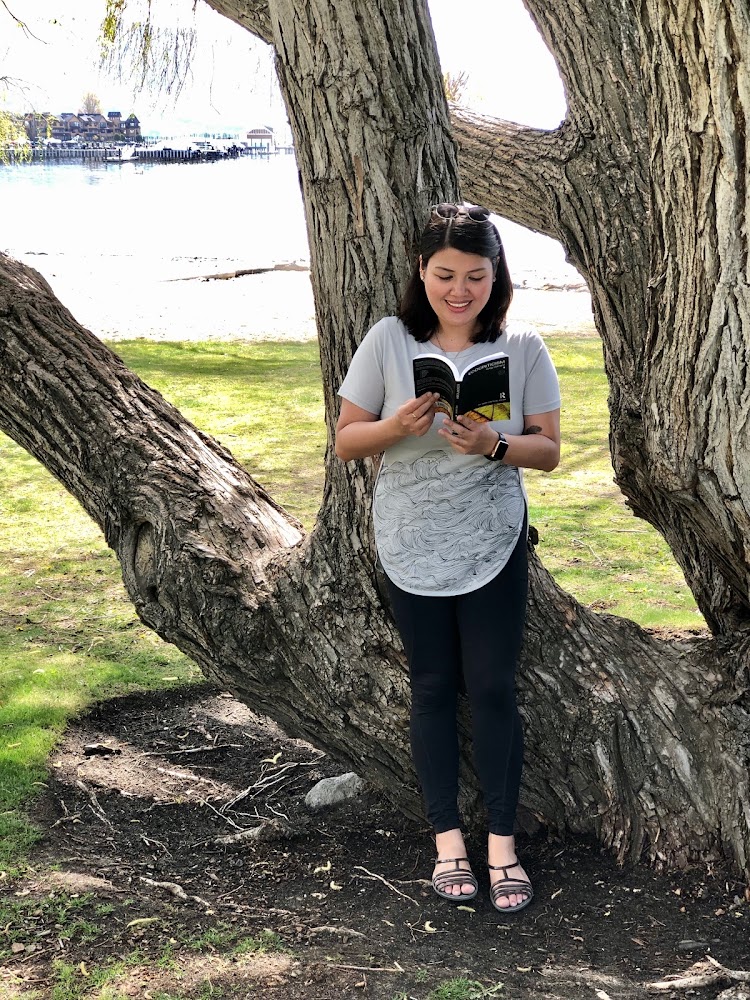

Popcorn City is what Rina Garcia Chua, a PhD student in her last year of graduate school and currently finishing her dissertation on ecopoetry and migrancy, has named her skinny pig enclosure.

Chua migrated from the Philippines to Canada—Kelowna specifically—approximately five years ago to attend graduate school at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan (UBCO). She applied for graduate school in Interdisciplinary Studies with a specialization in the environmental humanities in 2016, has been actively writing in the fields of ecopoetry and ecocriticism since 2014, and has even edited an anthology of ecopoetry titled Sustaining the Archipelago: An Anthology of Philippine Ecopoetry. She’s also currently working on a collection of poetry titled A Geography of Natural Hazards.

Now we’re sitting at her kitchen table drinking milk tea as she gives me her “less-than-three-minute elevator pitch” of her dissertation: “What I’m doing is an analysis of anthologies of ecological poetry all over the world and looking at the meta-narratives that are missing from the bigger narratives. I’m interested in those meta-narratives—those smaller narratives—because of the stories of migrancy that have built a lot of them.”

When I ask her why she chooses to focus upon ecopoetry rather than say, fiction, she says “we have a saying in writing: a novel is a marriage, a short story is a relationship, poetry is a one-night-stand.” She prefers the short-term, for lack of a better word, commitment that comes with writing poetry. She elaborates further: “It’s easier for me to articulate my feelings, thoughts, and ideas in poems—in a shorter form than in a longer form—because I’m not often comfortable delving into emotions. Poetry seems to be the right fit for me there, but poetry is the hardest to master.”

Chua also reveals to me her original intentions for her dissertation: “The focus on ecopoetry started because I do have an anthology of ecopoetry in the Philippines and I really wanted to branch out from that when I started my PhD. I wanted to do Philippine climate change novels and Canadian climate change novels, but my supervisor insisted that my strength is in ecopoetry. I’m not sure about that even until now.”

There seems to be a common thread in our conversation.

Chua is not afraid of a challenge (or two, or three, maybe four).

I ask her to tell me a bit about her personal journey and the obstacles she has overcome in order to get to this point in her life. The first challenge she discusses is being a single mother at a young age: “I think that was the biggest obstacle, just being judged in a Catholic country—a very strict Catholic country—about your marital status; knowing that it was right for me at that time not to get married but feeling the pressure around me.”

She ascribes much of her drive and high productivity to the fact that she “wanted to prove something to everyone else.”

The second challenge she discusses is migrating to Canada. She tells me “it’s not like what you see in the movies.” Although many of Chua’s friends opted to pursue studies in the United States, she chose to come to Canada to work with her current supervisor at UBCO. She initially thought that the Canadian experience would be very similar to that of the American experience but found that “it’s completely different.” According to Chua, this presents difficulties because “when you’re in the diaspora, you’re linked by your separation from the homeland, but there’s always that tension with Filipino-Americans thinking that their experiences speak for other experiences. Filipino-Americans and Filipino-Canadians get lost in that. So, [Filipino-Canadians] always get forgotten or there’s an assumption that the Canadian experience is the same as the American experience. I think I struggle a lot with that in my scholarship and when I’m within academic circles from home.”

What appears to bring Chua comfort through all of these challenges is teaching others and being within a community that she can serve, and that serves her, as well. Chua says that, while many of her friends pursued nursing as a career path, she decided to pursue teaching. She not only “loves teaching” but asserts “that’s really what energizes me to do the research that I want to do.” After sharing several of her other potential career paths with me, she simply says “I lie to myself if I say I want to do this or I want to do that. In the end, it’s always going to be a form of teaching or another.”

In addition to Chua’s obvious eagerness when it comes to facing a good challenge, there is another common thread that weaves in and out of our conversation: the importance of personal fulfillment and self-nourishment.

While discussing her choice to write upon ecopoetry and migrancy, as well as her desire to teach, Chua says “I have to go with what fulfills me the most and this fulfills me the most because it’s a little bit of everything and that’s kind of how I am: a little bit of everything.”

She does not only speak of fulfillment for herself but urges others to pursue what fulfills them the most, as well: “Pursue what fulfills you—as hard as that sounds—because, in my experience, whenever I pursued what fulfilled me, everything just fell into place weirdly.”

Chua gently reminds us that, yes, we deserve to be doing what we want to do.

We deserve to be doing what makes us happy.

Though Chua encourages others to grab at an opportunity when they have the chance, she advises that one should do so with a cautious hand. Speaking largely to persons of colour, Chua makes this insightful remark: “There are lots of opportunities right now. They’re creating opportunities for us in academia, which is great—that’s what they’re supposed to do—but I think the best thing to do is be as discerning as possible with these opportunities and make sure that you get something out of it. Do not be of service to institutions that will not give you back anything in return. It has to be a reciprocal relationship, even with academia. If they need you in the space, make sure that you get something, as well. We have to nourish ourselves, too, as persons of colour. We can’t just keep giving and be tick boxes on somebody’s diversity report.”

Chua’s final piece of advice aimed specifically at women—including all individuals who identify as women—is that “oftentimes, as women, there’s no end to our energies. We just keep on going because that’s how we are trained in the household: take care of kids, go to work, make dinner, you have to hold the household together. But no. There should be an end to our energy and we should always take the opportunity to nourish that, especially as women when we hold so much emotional, intellectual, and mental labour on our shoulders. Pause and nourish ourselves. You know, do what we want to do and not be defined by what society tells us to do.”

I’ve drank almost an entire mug of milk tea during our conversation.

Chua finished hers about halfway through.

She speaks so fondly of the idea of personal fulfillment and self-nourishment, but I wonder if she realizes her incredible capacity to nourish others, as well, with her hot drinks, stories from home and her journey, her ability to converse in general.

No wonder she wants to be a teacher.

Like she says, she’s made for it.