Inspiring Individuals: Rowan Helaine

A Conversation with Rowan Helaine

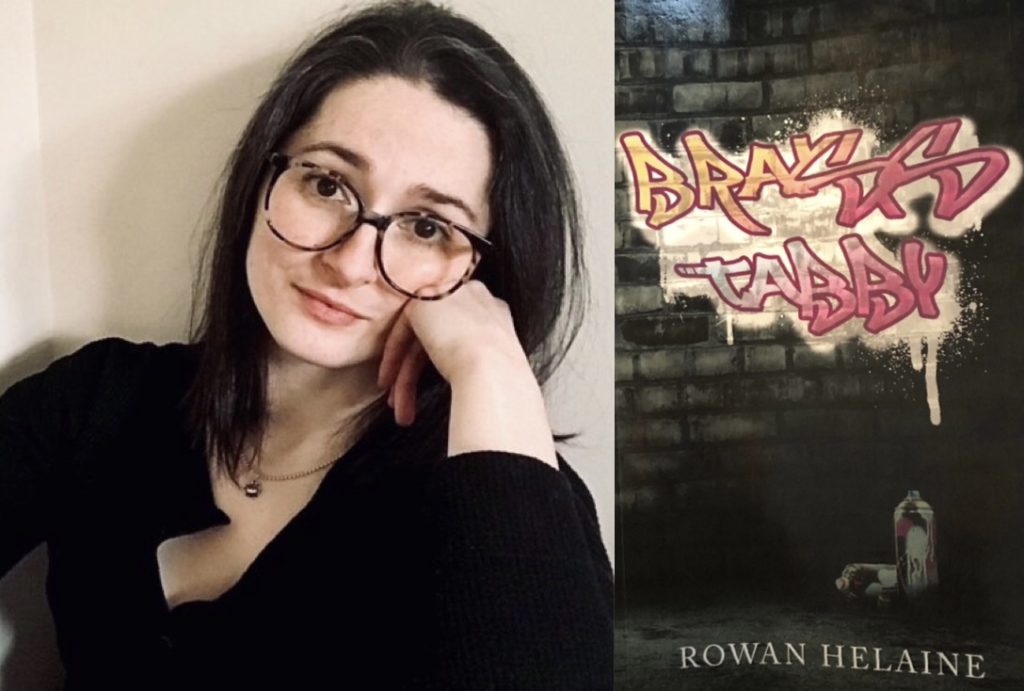

I must admit that a romance novel had never been on my bookshelf, in my home, or even in my hands until I received Brass Tabby (2021) just before Christmas of last year. When I picked up the novel, I couldn’t put it down and breezed through it in just over a week, which is quick for me.

I’m a slow reader. So, sue me!

Anyhow, something about this particular novel—perhaps it’s Enola Fothergill’s badass character introduction or her ability to exist as an independent individual despite her romantic entanglements with the dark and mysterious Grant Harcourt—excited me. I was so excited, in fact, that I reached out to the author, Rowan Helaine, and asked her to virtually sit down and chat with me about her experiences as a writer, character development, and how Brass Tabby is different than the stereotypical romance novel, particularly with its representations of women. To my delight, she agreed.

Because Helaine and I are both writers—of different sorts but writers nonetheless—of course I start off our conversation by inquiring about what inspired her to become a writer in the first place. Spoken like a true writer, she says that “as a very young child, [she remembers] having an overdeveloped internal monologue or inner life” and that she “[doesn’t] remember a time when [she] didn’t want to write something.”

Helaine is not just your average writer, though; she is a writer who creates with the intention of challenging oftentimes problematic representations of gender, specifically within the romance genre. According to Helaine, growing up she was “naturally drawn into the romance genre” but didn’t feel that she—and many women, for that matter—were accurately represented within it. She says: “I’m a happily child-free woman and—I can’t speak for everyone, but for me—I don’t remember a time when I ever wanted children. That’s a personal choice and journey for anyone to make, obviously, but some of the big overarching themes in the genre are big white wedding and babies. So, [with] a lot of people—child-free people, in fact—I’ve seen the common complaint [that] they hate reading romance because [they’ll] get to the epilogue of the story and…there’s always that blissfully pregnant woman or they’re planning their giant white wedding.”

Helaine makes it clear that she “absolutely support[s] a woman’s right to choose what to do with her body, how she wants to live her life, and who she wants to spend her life with” but that the picturesque scene of the white wedding and babies at the end of a stereotypical romance novel “just isn’t for everyone.”

So, noticing that “there’s this dearth of stories in the world—romance stories specifically—geared toward people who might not want that for themselves,” Helaine came to a decision: “I decided that, instead of just reading one hundred pages into a book and then throwing it across the room out of frustration or slapping it shut…I would just write the book I wanted to read. And so, I did.”

I find Helaine’s drive and motivation as a writer inspiring. I tell her so, and she insightfully responds with: “Don’t compromise. Never compromise.” This is a piece of advice I think we can all benefit from regardless of our individual situations.

After Helaine’s initial explanation of why she chose to pursue romance rather than any other genre, she shifts her focus to Enola Fothergill, the protagonist of Brass Tabby, and shares her reasoning behind creating such a character: “Society, at large, makes the mistake of treating women like they are incomplete without a romantic attachment, and it’s so unfortunate because we’re whole human beings regardless of who we’re ‘boning.’” Yes, you read that right. Helaine really used the word boning, and I enjoy and appreciate her choice of words. She continues: “So, it was important to me to write a character who was a fully formed human being with her own life and concerns and who was happy with herself. Maybe not necessarily happy with her economic situation but with herself as a person.”

In addition to creating a fully rounded-out female character, Helaine states that it was also “important…that [Enola] was willing to walk away from [Grant]” because “in so many romance novels, the guy will screw with the girl’s head and jerk her around and—let’s be honest—in real life if a man was jerking you around as hard as some women get jerked around in romance novels, you would lose his phone number and you would be right to.”

Helaine’s last note on Enola is a bit of a “self-revealing moment.” She says: “[Enola] didn’t feel like she was missing out on anything by not having a partner, and it was important to represent that to me because I have been in situations in the past where I have been treated like I’m less because I’m single. And oftentimes I feel like I’m happier single. I have more time for myself. I have more time to focus on my dog and my hobbies and write a whole damn book!” I don’t say it in the present moment, but I completely agree with her on this matter and I’m sure plenty of individuals can honestly say that they, too, have experienced more happiness being single.

Or is that just us?

The final question that I ask Helaine is if she finds it easier to write male or female characters—Enola or Grant—and her response surprises me: “I find it a lot easier to write male characters and I think that’s because, for a huge part of my career, I’ve been working in heavily male environments. It’s been my experience that oftentimes when you’re the only female in a group of men, they’ll come to you with all of their emotional shit because—at least in the cis world—there’s not a lot of safe spaces for men to unburden themselves and feel heard. Whereas, as women, we’re often encouraged to share and cry and all of those things that men are not allowed to do. So, for me, writing men has been easier because I feel like I’ve been given a little bit better insight into the male emotional spectrum.” She then admits that “writing women has been a challenge” for her “partially because, for a huge portion of [her] upbringing, [she] did not have the healthiest relationships with the females around [her].”

However, Helaine now describes herself as a “reformed anti-feminist” and finds “that the society of women and the support of women is invaluable.” Indeed, Brass Tabby is a novel built with feminist bones and held together by a couple critical female friendships. It’s much more than simply a romance novel: it’s a revolution within the genre itself.

And Helaine is just starting her writing career. She tells me that she is currently working on three more books and hopes to complete and publish at least one “in the next year.” Interestingly enough, she says that “at least one of them is outside the [romance] genre.” This leaves me wondering: now that she has revolutionized the romance genre, which genre is next?